Currently reading

While I often agreed with the authors chosen, I did not always agree with the specific books of these chosen as their "best" works.

I also personally would have re-arranged the genre sections to have a proper non-fiction section.

..and how come we are doing SF and thrillers, but no horror or fantasy? ...for heaven's sake - an iconic author such as Tolkien is included under children's fiction!? Surely the "children's" section could have rather been named: "fantasy" which could have included children's fiction.

Non-fantasy children's novels could have been placed in a YA section.

Alternatively, could SF/Fantasy not have been placed together, since there is often a lot of crossover between these 2 genres.

I did not like the "thriller" section either, which seemed rather skewed in favor of early twentieth century detective novels. (...and in spite of that, Miss Marple doesn't even feature, heh.)

Surely, in any case, one must view the books as 'must-read' only if you are interested in the specific genre, so I feel more genres should have been represented here.

On the plus side, for those having nothing else to do, and nothing left to read, every novel gets an informative, succinct description, with some brief information on it's author included, making this a useful and interesting, if lightweight reference/coffee table addition to one's library.

The book can be read on its own mainly for entertainment and to fill out any gaps in personal literary knowledge, or can be used as a quick reference book, but it is lacking regarding the satisfaction of anything more serious than idle curiosity, since it most often doesn't even give information on other equally good or famous books a prolific author might have written.

I couldn't manage to read all of this, but after trying for the fifth time and giving up, I had a dream.

I couldn't manage to read all of this, but after trying for the fifth time and giving up, I had a dream.In the dream, I get up and look in the mirror. My hair ...- oh, my hair! It's... really naughty hair. It insists on going in all directions while I sleep. So, I say a mantra every night: "Must flatten hair...must..."

..but it never works. I say it anyway. Who knows, one morning I might wake up with flat hair. This is a very important thing in my life. To wake up with neat, flat hair.

I know today is going to be a very important day for me. It's the day I'm going to meet him.

I just don't know it yet.

A whole lot of unimportant stuff happens, and then I walk into his office. I see HIM, and I trip over my own feet at the shock of it. ..at how magnificent, how sexy, how stunning, how manly, how masterful he is. ..and when he walks away, I trip over the coffee table because I cannot take my eyes off that tight butt in those tight pants.

A whole lot of other unimportant stuff happens, and then, he saves me from being my usual klutz self when I almost walk in front of a car, and then he kisses me. It's the first time I've been kissed, so I faint.

Then a whole lot of other unimportant stuff happens, and then I have a load of orgasms. So many orgasms, that I unfortunately cannot remember which one came first, (hehe heh, 'came' geddit?) plus I can't quite remember what came in between. Oh, yes. I have to eat certain food, and wear certain clothes, and work out at certain times of the day, and hmmm.. Well, anyway, that's what comes more or less in between the comes, I mean between the, between his, er.. between my.. umm. Between. Oooh.. Oooh. Aaah. Holy cow, I never knew that down there could be so between...so coming, I mean sooo holy ...I don't mean so full of holes -- okay, that as well,-- but, I mean, so filled up, with, with HIM.

Holy cum. I blush and chew my lip.

Oops! I hope I haven't given away any spoilers...

PS, I forgot to say. Now, I actually like my hair looking all fu..., I mean, looking like I had slept with somebody. (When actually, we weren't really sleeping, tee-hee!)

1

1

This is an online version of Chandler's introduction to semiotics in which he covers all of the basics in an extremely clear, lucid and accessible way.

As I said about one of his printed books: this is the ultimate introductory guide for those who tend to feel slightly lost at times when reading the works of the classic instigators of semiotics like Saussure, Peirce, Lacan, Foucault, Eco, Derrida and Barthes.

If you have an interest in semiotics/semiology, do yourself a favor and look the book up @ http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/S4B/semiotic.html

The fact that people are 'liking' this very rudimentary review, is shaming me into wanting to write more, but what to write about a subject so vast, and so potentially technical? Where does one start?

Perhaps one could try to sketch the basics and then perhaps an application or two?

See, the thing is that this subject is as huge as the world, because our entire world is made up of signs, and semiotics or semiology is the study of signs, of how humans interpret the world. So, in a certain way, one could say it is a branch of epistemology.

We can apply semiotics to almost anything, from linguistics, to psychology to the arts-- even to music. We can even look at signs in nature-- the signs and body-language animals make; although this is not the usual field of study of semiotics--it is most often applied in studying human culture and cognition; in studying the various ways in which humans make sense of the world.

To give an example of how it is applied, we could, for instance apply it to folklore (I quote from Chandler):

In... The Morphology of the Folktale (1928), Vladimir Propp interpreted a hundred fairy tales in terms of 31 'functions' or basic units of action.

Let's see how this works in practice using another example.

Remember [a:Umberto Eco|1730|Umberto Eco|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1319590745p2/1730.jpg] who wrote [b:The Name of the Rose|119073|The Name of the Rose|Umberto Eco|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1350764307s/119073.jpg|3138328]? Besides being a pretty cool author of fiction, he is also a semiotician. I'd been afraid of reading his work in this field (it looked frightfully complicated) until I came across a rather interesting subject of his study: the James Bond phenomenon.

Yip! Umberto Eco studied [a:Ian Fleming|2565|Ian Fleming|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1364532740p2/2565.jpg]'s James Bond. He wanted to try and figure out why Bond was such a huge hit. So he did a structural and contextual study of the James Bond novels.

Eco concluded that the novels were racist, sexist and prejudiced, for instance, against communists. The novels were written during the cold war when having "Reds" as your enemy was cool, and Bond stood for British arrogance.

So the novels functioned as a model of the world in which a British guy bested "Reds" all the time, but besides this, the narrative would follow a specific pattern. Eco identified 14 constant binary groups which would follow a specific pattern, as in: Bond as hero, Bond as victim, Villian as victim, the Soviet union, the Anglo-Saxon West, sexy female, etc.

Eco analysed the James Bond novels in terms of a series of oppositions: Bond vs. villain; West vs. Soviet Union; anglo-saxon vs. other countries; ideals vs. cupidity; chance vs. planning; excess vs. moderation; perversion vs. innocence; loyalty vs. disloyalty.

These would follow a "formula" as in : (I quote from Chandler:)

Umberto Eco interpreted the James Bond novels (one could do much the same with the films) in terms of a basic narrative scheme:

• M moves and gives a task to Bond.

• The villain moves and appears to Bond.

• Bond moves and gives a first check to the villain or the villain gives first check to Bond.

• Woman moves and shows herself to Bond.

• Bond consumes woman: possesses her or begins her seduction.

• The villain captures Bond.

• The villain tortures Bond.

• Bond conquers the villain.

• Bond convalescing enjoys woman, whom he then loses.

But I'm digressing from actual semiotics here with my Bond fascination. (Getting distracted while trying to talk about semiotics is pretty damn easy).

All right, so let me try to sum up the general areas of semiotics as they are divided into chapters in Chandler's book:... or no, nevermind, that may prove boring.

Let's say the main components are codes and signs.

Signs, according to semiotic theory, represent all our thoughts. Our thoughts are signs, because in our minds, we represent reality with thoughts --what we see and think and hear, are not the real things, but a representation of real things. So thoughts or words or images of a dog are signifiers and that which is being represented (the dog itself) is the signified.

Okay, so as you can see, this can be applied to a lot of areas: texts, photographs, visual art, film, language, and so on, and each area of application has its own set of signs and codes and terminology applying to those signs and codes, for instance when analyzing a photograph, we'd be looking at color, tone, lighting, 'vectors' (lines in the photograph) depth of field, and so forth.

We could, for instance, do a study of how violence is portrayed in various media. Get the idea how this field can just go on and on? Let me give an example of some codes: you get logical codes (maths, the alphabet, road signs), aesthetic codes (poetry, paintings, music, decor) and social codes such as dress codes ( Scotsmen wear Kilts, Bobbies wear a certain uniform, cheerleaders wear short skirts) or table manners; (we eat a hamburger with our hands, steak with knife and fork and Chinese with chopsticks ) and so on and so on.

Oh, wait, here is an interesting thing to quote out of Chandler. You know that picture that they included with the space probe Pioneer 10? It looks like this:

Per Chandler: The art historian Ernst Gombrich offers an insightful commentary on this:

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration has equipped a deep-space probe with a pictorial message 'on the off-chance that somewhere on the way it is intercepted by intelligent scientifically educated beings.' It is unlikely that their effort was meant to be taken quite seriously, but what if we try?

These beings would first of all have to be equipped with 'receivers' among their sense organs that respond to the same band of electromagnetic waves as our eyes do. Even in that unlikely case they could not possibly get the message. Reading an image, like the reception of any other message, is dependent on prior knowledge of possibilities; we can only recognize what we know.

Even the sight of the awkward naked figures in the illustration cannot be separated in our mind from our knowledge. We know that feet are for standing and eyes are for looking and we project this knowledge onto these configurations, which would look 'like nothing on earth' without this prior information.

It is this information alone that enables us to separate the code from the message; we see which of the lines are intended as contours and which are intended as conventional modelling.

Our 'scientifically educated' fellow creatures in space might be forgiven if they saw the figures as wire constructs with loose bits and pieces hovering weightlessly in between. Even if they deciphered this aspect of the code, what would they make of the woman's right arm that tapers off like a flamingo's neck and beak?

The creatures are 'drawn to scale against the outline of the spacecraft,' but if the recipients are supposed to understand foreshortening, they might also expect to see perspective and conceive the craft as being further back, which would make the scale of the manikins minute.

As for the fact that 'the man has his right hand raised in greeting' (the female of the species presumably being less outgoing), not even an earthly Chinese or Indian would be able to correctly interpret this gesture from his own repertory.

The representation of humans is accompanied by a chart: a pattern of lines beside the figures standing for the 14 pulsars of the Milky Way, the whole being designed to locate the sun of our universe.

A second drawing (how are they to know it is not part of the same chart?) 'shows the earth and the other planets in relation to the sun and the path of Pioneer from earth and swinging past Jupiter.' The trajectory, it will be noticed, is endowed with a directional arrowhead; it seems to have escaped the designers that this is a conventional symbol unknown to a race that never had the equivalent of bows and arrows. (Gombrich 1974, 255-8; Gombrich 1982, 150-151).

Gombrich's commentary on this attempt at communication with alien beings highlights the importance of what semioticians call codes. The concept of the 'code' is fundamental in semiotics. Whilst Saussure dealt only with the overall code of language, he did of course stress that signs are not meaningful in isolation, but only when they are interpreted in relation to each other.

It was another linguistic structuralist, Roman Jakobson, who emphasized that the production and interpretation of texts depends upon the existence of codes or conventions for communication (Jakobson 1971). Since the meaning of a sign depends on the code within which it is situated, codes provide a framework within which signs make sense. Indeed, we cannot grant something the status of a sign if it does not function within a code."

You get the idea. Hah, so much for the space drawing... oh well, it must have made the cosmologists launching the spacecraft feel good, or maybe it was done to impress the public?

Well, dear reader, hopefully I have included enough to give you a taste of both semiotics and of Chandler's intro to it.

I do understand if you decide it's all a bit much though, even broken up into simple bits a la Chandler. It is for me, I must admit - I can only handle so much at a time. Still, in my opinion, (but I am no semiotician, mind), this is one of your best bets to lead you into the world of signs. There are some good books discussing content analysis and discourse analysis out there of course, but to me, this work is as far I have found up to now, the most encompassing when it comes to the subject of semiotics in particular.

1

1

I didn't read all of it, but this is the ultimate introductory guide for those who tend to feel slightly lost at times when reading the works of the classic instigators of semiotics like Saussure, Peirce, Lacan, Foucault, Eco, Derrida and Barthes.

I didn't read all of it, but this is the ultimate introductory guide for those who tend to feel slightly lost at times when reading the works of the classic instigators of semiotics like Saussure, Peirce, Lacan, Foucault, Eco, Derrida and Barthes.

1

1

I feel cheated. I hate these wishy-washy anti-climactic Kay endings, and the wishy-washy over-virtuous flat characters, but that was not the only thing that disappointed me here.

I feel cheated. I hate these wishy-washy anti-climactic Kay endings, and the wishy-washy over-virtuous flat characters, but that was not the only thing that disappointed me here.I must say that although I loved most of the first three quarters, I hated the ending.

The book is supposedly based on the fall of the Northern Song Dynasty in China, and a lot of the background does indeed portray this.

Sure, there was a Chinese general who underwent a fate like this, but since Kay changed and embroidered upon so much of the detail anyway, couldn't he just as well have changed history to make the end more satisfying? ....or written a parallel history, a scenario of "what if?"

If you're going to make some famous characters your main characters, and you're going to diverge from what is known about them, why then not just as well, re-write a parallel history in a more pleasing, "what-if" format? Like for instance, what if a character chose not to follow orders at a certain point in time? How could that have changed history? (Since the author portrayed aspects of their personal lives differently, in any case).

Anyhow, I think that the actual Chinese legends and history associated with the birth and end of Yue Fei, are much more interesting than Kay's rendition of them.

Also, the technological and infrastructural developments of the Southern Song Dynasty and the establishment of the Ming dynasty would have made a cool second half to this novel which was all too rambling for what it covers.

I also hate his blooming sexism! It just grated on me how he repeatedly only talks about women as objects- Kay seems to have more insight into what a horse must be feeling and thinking when ridden, than all the women who were used and raped as the spoils of war, for instance. And what about the concubines- they're like paper puppets, not to mention his version of one of the greatest female poets in Chinese history. (Shan is based on the poetess Li Qingzhao.)

In fact, if you read up on the period, you will see that many upper-class women were pretty well-educated at the time, so as to better run their households, since they were in charge of the household and often mostly of the household finances too. Nothing of this is reflected in the novel, and the fact that Lin Shan can read and write is presented as something unusual, as "unfitting" for a woman.

Sure, Confucianism was repressive towards women, but not to the point that upper-class women were not allowed an education.

Female education was still subordinate to male education and women were subordinate to men (of course!), but Kay's women are like totally flat paper-cut-outs, like objects rather than people. Never does Kay successfully manage to see the world through a woman's eyes; we always just get a male chauvinist view of things.

Also, on the Northern Steppes women were not merely helpless sexual chattels. They lived a hard life and had to run the household when their menfolk were away. Some of these women even took on military roles. So, not quite the Gor-like view that Kay paints of women being literally mindless animals.

I've been musing about why Kay's apparent sexism seems to grate on me so, and I've realized that a lot of it might have to do with the fact that I've recently been reading a lot of the work of author China Mièville, a male author who manages to present a remarkably non-sexist view of the world in comparison.

I've become spoilt!

Another niggle (not all that important, but really irritating), are all the banal platitudes, for instance: "It was an important day. Some days are", and the foreshadowings that never truly materialize, all the hints about legends in the making and so on.

-----

When the west wind blows the blinds aside,

I am frailer than the chrysanthemums. --Li Qingzhao (Li Ching-chao, 1084-1155)

Despite what Kay says, I think she is exquisite! ;) ..and quite contrary to the image Kay creates, Li Qingzhao's mother was a poetess too.

The 'real' Li Qingzhao actually loved her husband very much, and by all accounts they had a very happy marriage, sharing many interests. After the fall of the Northern Song dynasty, while they were fleeing the Tartar invasion, he died of typhoid fever.

Li Qingzhao mourned her husband's passing unto her death. She also greatly mourned the world that existed before the Tartar invasion.

It is very difficult to translate the artistry of Chinese poetry into English, since a large part of the artistry lies in how the Chinese characters are rendered and 'fit in' with one another colloquially and idiomatically-- so attempts to translate to English loses a lot of the essence of what is admired in most of these poems; a bit like how it would be hard to translate things like alliteration and assonance and 'puns' from English into another language.

Nevertheless, the sadness in her later poetry shines through the translation process.

Fading incense, remnants of wine:

A heart full of remorse.

Parasol-leaves falling,

Parasol-leaves falling-

Urged by the west wind.

Haunting me always,

Autumn's somber colors.

Never leaves me alone,

The pain of loneliness.

------

LATER: I've been trying out some of the standard fantasy fare out there in the past day or so, which has greatly increased my appreciation of this novel. It might not be great literature (I've been reading the likes of Proust, Mann and Nabokov, previously, so the bar is high), but I do reckon that with the exception of really original writers like Mièville and a few others, at least this is pretty good fare for the fantasy genre.

True, the novel does have a badass character who can kill 7 men in a few seconds with a bow, but except for that, at least this is something refreshing compared to "standard" fantasy fare. My other gripes still apply though. But I do love the setting of the novel, and now that I've gained some distance, I feel more happy that I spent time reading this novel.

It's hard to avoid politics, and in particular, Mièville's politics when it comes to Bas-lag. In Mièville's Marxist oriented doctoral thesis, [b:Between Equal Rights: A Marxist Theory of International Law|68502|Between Equal Rights A Marxist Theory of International Law|China Miéville|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1354903611s/68502.jpg|1963235], he argues that international law is fundamentally constituted by the violence of imperialism, which by implication, is driven to a large extent by capitalism.

It's hard to avoid politics, and in particular, Mièville's politics when it comes to Bas-lag. In Mièville's Marxist oriented doctoral thesis, [b:Between Equal Rights: A Marxist Theory of International Law|68502|Between Equal Rights A Marxist Theory of International Law|China Miéville|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1354903611s/68502.jpg|1963235], he argues that international law is fundamentally constituted by the violence of imperialism, which by implication, is driven to a large extent by capitalism. It's not too hard to work out that New Crobuzon is the theoretical capitalist "bad guy" of Bas-lag with its secret police and under-handed politics, its economic avarice and totalitarian leanings. And yet, its antagonist in the plot of the novel, The Scar's floating city community of ships-made-into-a city, Armada, are thieving, murderous pirates who forcefully take their future citizens by violence, and brainwash them into submission, or else simply kill them. They're not good guys either by any measure in my book. The reason why Armada is supposedly a 'good' community, is because they set erstwhile prisoners 'free' (not really free if they're not allowed to leave, are they?) to become good non-law-abiding pirates who kill and pillage.

So once again, Mièville presents us with a complex, politically grey, ambiguous scenario.

I agree that totalitarianism (as represented by New Crobuzon) is undesirable, but I'm not so sure that imperialism always is 100% bad (The Chinese and Roman empires brought a lot of benefits to its citizens, for instance - most of the time, that is, when the rulers weren't going crazy), and I'm known to be pretty much anti-anarchist, depending on what your definitions are. (In other words, I believe in having at least some universally agreed-upon laws being in place which human societies need to follow and orient themselves by; and it is important that whatever the law is, that it not be enforced on an arbitrary basis. ) The Scar forces one to ponder on these aspects when you get acquainted with how Armada is run, and I reckon this is a good thing.

In any case, I don't see New Crobuzon as being any the more imperialist or less violent than Armada is--in fact the latter seems more so to me. At least the citizens of New Crobuzon are free to leave the place if they don't want to live there anymore...

I think my dislike for these aspects of Armada, is part of the reason (there are others such as a feeling of sloppiness in the plotting and general writing) that makes The Scar my least favorite Mièville. Perhaps a certain coarseness in how the uncouth aspects of the world was presented, also played a role.

Granted, Bellis Coldwine, the main character, seems to agree with my feelings regarding Armada; so perhaps I should actually be giving Mièville extra points for embracing ambiguity and avoiding a black-and-white scenario. After all, life is as he describes it - he makes no attempt to present any whitewashed utopias, as far as I can see.

One thing that Mièville and I probably can agree on, is that when naked greed gets to run its course unchecked, social injustices mount up. ...and this is so whether there is a communist or a capitalist regime at the helm.

PLOT

Back to The Scar, I really enjoyed all the surprises and twisting towards the end, and that the actual 'solution' was a lot more political and pragmatic than one tended to believe earlier on in the novel. The twists and surprises alone pushed me to give the book an additional star.

WORLD-BUILDING

I think that Mièville again tried to pack in too many weird creatures and small disconnected bits of world exposition, much as he did with Perdido Street Station, but it does make for a richer world than, for instance his much more tightly controlled The City & The City, which is a quite good novel by detective genre standards.

He did lose marks for the mosquito women's unnecessary bits of anatomy, which made even less sense than the cactus women's. Maybe breasts are Mièville's way to distinguish between the sexes; and yet, he seems remarkably non-sexist when it comes to most of his female characters, including Bellis Coldwine, the main character in The Scar.

Oh! There's so much going on in this novel, that I almost forgot about how Mieville plays around with quantum physics and metaphysics with his "possibility leaks". I really enjoyed that aspect.

CHARACTER BUILDING

I liked it. I thought Tanner and Bellis and Shekel and Johannes and Silas and Uther and The Lovers and Brucolac were all believably portrayed, and in spite of Bellis being portrayed as an emotionally "cold" person, one gets to see enough of why she is like this, and enough to gain empathy with her need to protect herself by endeavoring to remain as detached as possible.

BOTTOM LINE

In spite of the fact that the novel lags and wanders about rather aimlessly in places around the middle, as with the first book in the series, Perdido Street Station, it is worth hanging on for the roller-coaster ride towards the end, so I added a star here and subtracted a star there, and came up with three and a half stars for The Scar, a novel with distinct strengths and weaknesses.

----

For an extra bit of spice which might be appreciated by those who have read quite a bit of Mièville, read on. If you don't have a sense of humor, don't read on.

Ladies and gentlemen, there is a first time for everything, they say, even for writing erotica into a review. Especially if it is sado-masochistic erotica. Well, see, China Mièville put me up to it while I was reading his novel The Scar.

I was reading this passage in The Scar, you see, of sado-masochistic passion between two lovers, (part of the exploration on the theme of scarring, btw) and slowly an image began to form in my mind, of me somehow managing to find myself in a room, with a naked China Mièville, who was clad only in a slave-collar, the chain of which I was holding. I had a whip in my other hand.

There was a pole in the middle of the room, and I bade China to face this pole, his back to me. “Look at the pole, China!” I said as I raised my whip.

“I want you to understand something, China!” I snapped curtly, tickling his flank with the end of the whip. And that is how I feel about the word ‘puissant’”.

I flicked my whip with puissance, and then brought it home puissantly.

*WHACK!* “OW!” China jumped a little. “Good! I see the message is getting through to you. That one was for all the puissants. And this one...” *WHACK!* is for all the puissance. "

China did not cry out this time, though he did flinch. Two pink marks striped his muscled glutes.

"You also deserve a smack for all the sloppiness, and for the flopping about between tenses. I mean, really, where were you when the grammar class did tenses? ..but as usual, you're doing your own thing again, making up the rules as you go along...

Since it should be your editor getting the whack for a lot of this, I'll just give you a little smack, with much less puissance than previously. " *Smack*

“...I’m not done yet, China, I happen to have read quite a few of your creations. Remember ‘palimpsest?’(Though admittedly your love for the word is less obvious, though obvious enough, than for 'puissance'). Well, I’m going to make a little pink palimpsest here on your beautiful behind."

I could see China’s body tighten and I imagined him inwardly steeling himself. Petty cruelty got the better of me and I smirked. “Do I sense a certain recognition, Dr Mièville?

*WHACK!* “ For PALLIIIMMMMPPPSSSESSST!” I yodelled.

“ ...and just to make the palimpsest complete, here is one for all the drooling in The Scar specifically. ( *whackety*) Now, have I left anything out?”

I tapped my high-heeled leather boot impatiently, masking my pleasure at finally getting my revenge in regard to the niggles and especially the puissance, wondering inadvertently if I myself was not perhaps drooling by this point.

China turned to face me, a ghost of a smile on his sexy lips, a twinkle in his eye. “ Wipe that smile off your gibbet!” I roared, whacking him one on the arm for good measure. "And, by the way, that last whack was because the mosquito women have breasts. Mosquitoes lay eggs--what the Jabber would mosquitoes need breasts for?"

At that, he grabbed hold of the whip and twisted it easily out of my hand. “You know what you need?” he asked, grinning openly. “A good lesson in creative writing.”

Of course, the rest of the fantasy is censored for the benefit of the large warrior woman, so we'll talk a bit more about The Scar after the cold shower break.

*Takes a cold shower*

**Disclaimer: The S&M "erotic" scene in this review bears no implication whatsoever as to the orientations or inclinations of either the author of this review or of the author of the novel under review; it is meant to be humorous, and has no bearing on reality whatsoever.

LOLITA

This review contains SPOILERS, but if you've been living on this planet, you probably knew about them already...

Daddy, are we there yet? Are we there YET? Daddy, how much longer still? I want to go home!

Hush little one, now

Say your prayers

Don't forget my little nymph

To include everyone

I tuck you in

Warm within

Keep you free from sin

'Til the sandman he comes

Sleep with one eye open

Gripping your pillow tight

Exit light

Enter night

Take my hand

We're off to never never-land

Something's wrong, shut the light

Heavy thoughts tonight

And they aren't of snow white

Dreams of war

Dreams of lies

Dreams of dragons fire

And of things that will bite, yeah

Sleep with one eye open

Grippin' your pillow tight

Exit light

Enter night

Take my hand

We're off to never never-land

Now I lay me down to sleep

Pray the lord my soul to keep

And if I die before I wake

Pray the lord my soul to take

Hush little baby don't say a word

And never mind that noise you heard

It's just the beast under your bed

In your closet in your head

SOUNDTRACK AND VIDEO:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CD-E-LDc384

Vladimir Nabokov slyly catches the reader in plenty of traps with his twisting perspectives in this wrenching tale of brokenness, passion, insanity, obsession, and, ... love?

VERY SHORT PLOT DESCRIPTION:

A broken, sociopathic middle-aged man with strong pedophilic tendencies, plots, lies and connives his way into gaining control over a pubescent 12-year old orphan girl, and intimidates and bribes her into having daily sexual relations with him, until she manages to escape, and then...? Well, this is where the plot thickens, and where the novel's real punch lies.

CHARACTERIZATION IN THE NOVEL

The characterization, these shimmering, phantasmagorical mirages that are Humbert Humbert and Lolita, this is where Nabokov has exhibited pure genius. We initially see Lolita only through the eyes of Humbert, our typical unreliable narrator, so the reader has to constantly "read between the lines" to try and figure out what is really going on with the girl, and Nabokov does a beautiful job of creating a sympathetic portrait of the trajectory of a painfully tragic young life.

As for Humbert, from the outset one gets the impression that Nabokov is toying with the reader, when he introduces us to Humbert, creating the perfect unreliable narrator who even, right from the start, mentions that he has been institutionalized for bouts of insanity, also showing his sociopathic side by mentioning the games he likes to play with psychiatrists and therapists. He also makes no bones about the fact that he is a raging pedophile who can barely restrain his lust at the sight of 9-12 year old girls.

So, definitely not a sympathetic character. Plus there is ample reason to distrust him and to watch out carefully for inconsistencies in his version of events. Indeed, inconsistencies in what Humbert tells us, are rife.

Watch carefully what he tells us at the start of the novel, and see how what he says tends to be contradicted later on either by himself, or by what the other characters tell us.

Nabokov lays it on so thick, that Humbert, who finds 17 year olds abominably "aged", and who talks about a fourteen-year old as :" my aging mistress", appears almost like a caricature.

Humbert nurtures a fantasy that a large amount of pubescent and pre-pubescent girls are dangerous demonic little seductresses just ripe and waiting to be picked, whom he dubs "nymphets".

There is a lot not to like about this character for most of the novel: In the first sections of the narrative, one learns that he sees women (and actually all humans, for that matter) merely as vehicles to further his own pleasure, to be disposed of if they don't serve his personal interests in some way.

He is uncommonly uncharitable towards his first wife, as a start. He sees all little girls purely in terms of how sensually appealing and therefore potentially sexually satisfying they may be for him. He often fantasizes about visiting violence and even death upon those that get in the way of his needs. You think to yourself what a misogynistic, uncharitable, selfish, violent, conniving, sociopathic freak this narrator is. How much more hateful can a writer make a character?

Quite a bit more, it would appear, as one reads on. Humbert marries the hapless Charlotte, being in her thirties much too old for his tastes, for the sole and only reason to get to her "nymphet" daughter of twelve, and here enters an interesting ingredient of the novel, being Nabokov's use of irony.

IRONY

Humbert plots to kill Charlotte to get her out of the way, at which point Nabokov's bits of ironic black humor in the form of fate's role, humorously referred to by Humbert as "McFate", comes to the fore.

It turns out that if Humbert had followed through with drowning his wife as planned, he would have been spotted by the local landscape painter, and therefore he was "saved by the bell" of his own inaction. Fate then "rewards" him when his wife, blinded by tears when she finds out about his secret passion for her daughter after reading his diary, runs in front of a car and is conveniently killed.

After spinning a web of lies and connivances, Humbert is now finally free to fetch his stepdaughter from summer camp in order to "enjoy" her.

He plans to feed her nightly doses of sleeping pills in order to rape her in her sleep, but once again Mc Fate intervenes, and after finding that the sleeping pills don't work, Humbert is delighted when Lolita willingly submits to him. ..or did she? Throughout the novel, Nabokov spins a shimmery web of illusion. How much of what Humbert says is true? After all, we already know that he is a lying, conniving sociopath, right?

Mc Fate keeps intervening in interesting ways, but fate is not the only source of irony in the novel. Another source of irony, for instance, is the way that Humbert views himself.

One of the tongue-in-cheek aspects of Humbert's character is his narcissism. Right from the start, Humbert keeps referring to his own "good looks" but Nabokov cleverly makes the reader aware that he is actually a huge, thick-fingered, hairy dark beetlebrowed creature resembling an ape.

He also constantly speaks of his: "polite European way" while we realize that he is actually just a dork.

AMBIGUITY AND DOUBT

When Lolita, who had apparently already lost her virginity to some young boy before Humbert has intercourse with her the first time, says, later on, that Humbert had raped her on that first day, is she merely being playful, or is this a clue towards what had really happened? Why does Lolita have to be bribed into every caress, bullied into every act of intercourse-- into "doing her duty" as Humbert sees it, just as if she were his little medieval wife and owed him a wifely duty. (A 'right' which he claims very often, to the poor girl's chagrin.) Why, if she was really happy to go along with things, does Humbert have to keep threatening her, why does he refer to her as his captive?

Through his genius, Nabokov does not immediately reveal these clues, he sows increasing seeds of doubt throughout the text as one progresses with the plot.

Only in increments, does one see the damage that is being done to Lolita.

The first thing one realizes, is that Humbert is robbing her of a sizable portion of her education, as he keeps her out of school for at least a year on road trips designed to camouflage the fact that what he was actually after, was to have sexual relations with the girl as much as was practically possible.

As their life together progresses, Nabokov shows how she is being deprived of the normal social development so crucial to humans in this early phase of life, as Lolita starves for young company, and eventually for *any* company outside that of Humbert's oppressive presence.

Toward the end, Humbert relents regarding his descriptions of Lolita as an evil seductress when he admits that Lolita is actually a "conservative" person, deeply damaged by the incestuous nature of their relationship. (While she was under his control, Lolita was coerced to act as if the couple is father and daughter, creating a psychologically incestuous situation, which must have added to her confusion and increased the sense of helplessness at being left a sudden orphan.)

Who could Lolita have gone to, where to for help? Humbert kept pressing on her the idea that if she were to "tell" she would lose her freedom and end up in the equivalent of a prison for children.

PROSE

Vladimir Nabokov wrote:

"My private tragedy, which cannot, and indeed should not, be anybody's concern, is that I had to abandon my natural idiom, my untrammeled, rich, and infinitely docile Russian tongue for a second-rate brand of English, devoid of any of those apparatuses — the baffling mirror, the implied associations and traditions — which the native illusionist, frac-tails flying, can magically use to transcend the heritage in his own way."

Well, let's just say that if Nabokov's Russian prose is even more idiomatically apt, readable, and beautiful than his "second-rate" English prose is, then I oh so wish I was fluent in Russian so that I could read him in Russian! I would subtract half a star for all the French inserted into the text, though, which is fine, since I gave the novel six stars to start with.

PLOT RAMBLE

Something else I would subtract half a star for, is the rather undisciplined way in which paragraphs of woolly rambling which does not further the plot (or really anything else) were not excised.

TWISTY DÉNOUEMENT

Beautiful, riveting prose aside, the real genius of this novel becomes apparent towards the end. Plotwise, I had expected different things to happen. For instance, possible outcomes which did not materialize, I had expected Lolita to become pregnant with Humbert and become a tragic child-mother. Another possibility I might have expected, would be Humbert having shot Lolita in revenge after she ran away.

There are many possible ways in which this novel could have ended. The most unexpected thing that happens, though, is the character growth/character revelation one experiences both regarding Humbert and Lolita. For the first 80% of the novel, I never, ever, in a month of Sundays, could have imagined that I could feel the slightest twinge of sympathy for such a selfish, deluded, depraved monster such as Humbert.

...and yet, as we start to see him suffer, really suffer, faint twinges start to ripple under the surface.

For the first 80% of the novel, I fully believed, as did Humbert himself, that he was simply a sex-crazed fiend, completely incapable of anything even closely resembling love or empathy. After all, for all of his self-professed tenderness, he knew full well that he was keeping Lolita a prisoner against her will; knew that he was making her miserable, knew that what he was doing, was not only against the law but was morally wrong as well, inasfar as human judgement of affairs go, and never gave a thought to her well-being beyond her role as a vehicle of his pleasure.

For most of the novel, Humbert merely uses adult women as a front while he was indulging in his voyeuristic fantasies with multiple schoolgirls. Humbert maneuvering himself into a position where he could ogle prepubescent girls at play whilst masturbating in some way, through frottage or whatever means, becomes a familiar theme, not least sickening of where he makes Lolita stimulate him genitally whilst he is ogling "other nymphettes". (One can only conjecture how this must have made her feel). ..and Humbert makes it very clear that his attraction towards Lolita is simply as one girl-child amongst many, he is constantly sizing up the charms of other girls, even with Lolita at his full sexual disposal.

In one of the most offensive phrases to be found in the world of fiction, Humbert says:

" I now think it was a great mistake ... (not to) marry my little Creole; for I must confess that I could switch in the course of the same day from one pole of insanity to the other — from the thought that around 1950 I would have to get rid somehow of a difficult adolescent whose magic nymphage had evaporated — to the thought that with patience and luck I might have her produce eventually a nymphet with my blood in her exquisite veins, a Lolita the Second, who would be eight or nine around 1960; indeed, the telescopy of my mind, or un-mind, was strong enough to distinguish in the remoteness of time — bizarre, tender, salivating Dr.Humbert, practicing on supremely lovely Lolita the Third the art of being a granddad.

This passage reminded me of the Fritzl case , which took place after Lolita was written, so, truth may still be stranger than fiction.

Another thing which made me really hate Humbert, was where Lolita becomes ill with bronchitis and is consumed with fever, and he nevertheless does not desist from having sexual intercourse with her.

A passage that I found exceedingly creepy reads as follows:

" How sweet it was to bring that coffee to her, and then deny it until she had done her morning duty. And I was such a thoughtful friend, such a passionate father, such a good pediatrician, attending to all the wants of my little auburn brunette's body! My only grudge against nature was that I could not turn my Lolita inside out and apply voracious lips to her young matrix, her unknown heart, her nacreous liver, the sea-grapes of her lungs, her comely twin kidneys. " .

Beside the exceeding creepiness of the vivisection image, note the dark sarcastic irony of the second sentence. Not to mention, in the first sentence, the irony about servicing Humbert being Lolita's "duty"!

Yet another thing that struck me, was how Humbert never seemed to give a thought about how much Lolita's mother's death must surely have traumatized her, though he certainly cashed in on her helpless status as an orphan.

So, despite one knowing that Humbert was intentionally painted as a caricature of a heartless, selfish, callous, duplicitous sociopathic monster, (Humbert even makes it clear from the start of the novel, that he is a murderer - one only learns the identity of the victim at the end) it speaks of Nabakov's genius that, as things start to fall apart for Humbert, one actually feels the twinges of a softening in one's attitude towards him.

And then comes the twist in the final scene between Lolita and Humbert. All along, I had been primed by Nabokov's clues to believe that Lolita, although a brash, impudent youngster, had been innocent of many of the things Humbert had suspected her of - since he himself questions his own sanity and writes off a lot of his suspicions to paranoia.

The first clue that Humbert really has no clue about his own psyche or reality out there, is when Lolita indeed does escape with the help of an outsider. But then, in that final confrontation, the famous phrases as uttered by Humbert:

"...and I looked and looked at her, and knew as clearly as I know I am to die, that I loved her more than anything I had ever seen or imagined on earth, or hoped for anywhere else.

She was only the faint violet whiff and dead leaf echo of the nymphet I had rolled myself upon with such cries in the past; an echo on the brink of a russet ravine, with a far wood under a white sky, and brown leaves choking the brook, and one last cricket in the crisp weeds... but thank God it was not that echo alone that I worshipped.

What I used to pamper among the tangled vines of my heart had dwindled to its essence: sterile and selfish vice, all that I canceled and cursed.

[...]

I insist the world know how much I loved my Lolita, this Lolita, pale and polluted, and big with another's child, but still gray-eyed, still sooty-lashed, still auburn and almond, still Carmencita, still mine;[...]

No matter, even if those eyes of hers would fade to myopic fish, and her nipples swell and crack, and her lovely young velvety delicate delta be tainted and torn — even then I would go mad with tenderness at the mere sight of your dear wan face, at the mere sound of your raucous young voice, my Lolita.

At last we see some humanity in this ghastly caricature of a character, and it is a humanity that tears at your soul, when you realize along with the character himself, that he has finally transcended the narrow confines of his selfish myopic obsession with youth and young girls, when he declares that, even heavily pregnant, even as an adult, even when stripped of her youth, he loves Lolita, and will continue to love her and wants to spend his life with her, even when she has lost all vestiges of that youth that he had worshiped so.

It is almost with shock that ones realizes how much the narrator's viewpoint has matured at last towards recognition of his culpability, towards responsibility for his crimes, when he intuits Lolita's thoughts:

"She groped for words. I supplied them mentally (" He (Clare) broke my heart. You (Humbert) merely broke my life")."

..and now, seeing her trauma and brokenness before him, it finally presses on Humbert's mind how helpless Lolita must have been feeling all along, and how hopeless her situation:

"I happened to glimpse from the bathroom, through a chance combination of mirror aslant and door ajar, a look on her face... that look I cannot exactly describe... an expression of helplessness so perfect that it seemed to grade into one of rather comfortable inanity just because this was the very limit of injustice and frustration..."

...and, after we had watched with horror the final dissolution of his character in the tragicomic events at the end of the novel, in which he can be seen as symbolically killing the bestial aspect of lust in a supreme act of violence, his final parting words mitigates the monster:

" Had I come before myself, I would have given Humbert at least thirty-five years for rape, and dismissed the rest of the charges.

I wish this memoir to be published only when Lolita is no longer alive.

...one wanted H.H. to exist at least a couple of months longer, so as to have him make you live in the minds of later generations. I am thinking of aurochs and angels, the secret of durable pigments, prophetic sonnets, the refuge of art.

And this is the only immortality you and I may share, my Lolita.

In Lolita, Nabokov takes an extremely uncomfortable subject by the scruff of the neck, and turns it into a tour de force of modern literature.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qTEThUO__Uo

ADDENDUM: ..but how do we know that what Humbert says at the end, is really genuine?

Throughout the novel, it is less helpful to listen to what Humbert says, than to look at what he does. Previously, he had acted in immeasurably selfish ways, right up to the point where he set out to take revenge with a gun in his pocket. Yet why would he need to take so much money with him? He knew that Lolita was older now, not a 'nymphet' anymore, so, if his motive was pure selfish revenge, why the money?

One has to carefully consider the evidence placed before you, and then you will see that the final actions HH took before he was taken into custody, point towards a huge shift in his attitude from being focused inward on himself, toward finally truly caring for the one he had falsely claimed to love so often before.

Since the piece is well known as being a landmark work of fiction regarding male homosexuality, I am not going to focus on that in my review, or on its other element that has been flogged to death as well, being the rather extreme youth (age 14) of the love object.

Since the piece is well known as being a landmark work of fiction regarding male homosexuality, I am not going to focus on that in my review, or on its other element that has been flogged to death as well, being the rather extreme youth (age 14) of the love object. -----

Well! What a conflicting piece of fiction. The novella seems fairly divisive amongst critics, but one thing that I think most of us can agree on, is that the novella is a discomfiting piece of writing. I suspect this was so for the author as well as for his readers.

For me this was not because of how the protagonist's obsession affected his love-object, but because of how this obsession affected the protagonist himself.

... and, I couldn't shake the feeling that the novella was pretty much autobiographical in many senses. (I found out later that it was so in many respects, and the love-object is based on a real person. Most uncomfortable of all, is that the 'real' Tadzio, was the 10-year old Wladyslaw Moes).

Achenbach, the protagonist, is a well-respected author, who, like Mann, tends to engage with political and intellectual issues in his work. Like Achenbach, Mann visited Venice, where he made the acquaintance of a young boy whose beauty he apparently admired; with the difference that Mann was accompanied by his wife and brother, while Achenbach was alone. Okay, there are a few other differences as well - and one pretty large one, but that's a spoiler.

Many reviewers and critics have made much ado about the protagonist's homosexuality and/or his pederastic inclinations, but I think what disturbed me most was the stalker-ish intensity of the protagonist's infatuation, and to an extent also how he totally overromanticized the idea of physical beauty, using purple prose and overblown idealistic sentiments to describe his thoughts on physical human beauty, (which I deeply disagree with), and which Mann propped up with symbolism from Greek mythology, and references to Platonic ideals.

Ironically, Björn Johan Andrésen, who played the role of the fourteen-year-old Tadzio in Luchino Visconti's 1971 film adaptation of Death in Venice, is credited with saying: “One of the diseases of the world is that we associate beauty with youth. We are wrong. The eyes and the face are the windows of the soul and these become more beautiful with the age and pain that life brings. True ugliness comes only from having a black heart”.

Because I have long known that beauty is only skin-deep, I like those sentiments a lot better than:

... he believed that his eyes gazed upon beauty itself, form as divine thought, the sole and pure perfection that dwells in the mind and whose human likeness and representation, lithe and lovely, was here displayed for veneration. This was intoxication, and the aging artist welcomed it unquestioningly, indeed, avidly. His mind was in a whirl, his cultural convictions in ferment; his memory cast up ancient thoughts passed on to him in his youth though never yet animated by his own fire. Was it not common knowledge that the sun diverts our attention from the intellectual to the sensual? It benumbs and bewitches both reason and memory such that the soul in its elation quite forgets its true nature and clings with rapt delight to the fairest of sundrenched objects, nay, only with the aid of the corporeal can it ascend to more lofty considerations. Cupid truly did as mathematicians do when they show concrete images of pure forms to incompetent pupils: he made the mental visible to us by using the shape and coloration of human youths and turned them into memory's tool by adorning them with all the luster of beauty and kindling pain and hope in us at the sight of them...

Some interesting thoughts there, though I disagree with the sentiments expressed in bold. Were these the thoughts of the protagonist, or the author himself? From his notes, it would seem that these were actually Mann's own sentiments. They do seem a perfect rationalization for a man in Achenbach's position to make though, which makes them pretty fitting in their context, I must concede.

I am surprised that so many people, with so much evidence to the contrary, can still invoke Plato's ideas of essence = form when it comes to physical beauty = spiritual beauty. Surely, it doesn't require too much contemplation to come to the conclusion that physical beauty does not equal spiritual beauty?

One could muse that perhaps what Achenbach is rather saying, in what seems like a rationalization for his passion, that beauty can inspire love, the latter which is in itself beautiful. ...and yet, since in this specific context the object of that passion is so young, and vain, and since they had never even exchanged a word with one another, could this be love? Methinks not - this could surely be but an infatuation of the senses.

From the notes Mann made for the writing of the novella, it is clear that part of what he wanted to show, was that an artist (an author like himself) cannot be a dignified, purely rational creature, that he needs to be in touch with his passions and emotions, and that the act of creating art is inherently not a dispassionate activity.

Something else that Mann seems to be saying behind the scenes, is that love itself cannot be dignified, that love pushes an individual into undignified behavior.

Mann being a fairly obviously repressed individual, one can read a certain parallel between the disease that infects Venice, with Achenbach's almost insane passion (insanity features in Mann's notes). Mann seems to see these homosexual pederastic impulses that one surmises he felt himself, as at the same time degrading and ennobling. Ennobling, so the reasoning seems to go, in the sense of that when a person degrades himself for love, it can be seen as a kind of sacrifice of dignity for a higher cause (being, in this case, "love").

But one can only follow such reasoning if you can agree that a passion that seems so distant, unrealistic and physical can be ennobling and can be described as "love".

To put the matter in a slightly different context - make a small leap in your mind and imagine that the love-object here is instead a 40-year old woman. If the latter was the case, would the scenario in DIV still be creepy? Indeed, it would. What would make the scenario still creepy? It would still be a purely physical obsession characterized by stalkerish behaviour.

So one ends up asking yourself how far selfishly and obsessively stalking someone can really be an expression of love? ..and if it is to the extent that one puts this behaviour of yours above the wellbeing of its object? ..and what when the continuation of this behaviour puts the other's life in danger, then is it not actually selfishness and the opposite of love?

Achenbach deliberately does not tell Tadzio's mother about the epidemic in order to avoid the outcome that Tadzio's family would leave the resort; which would remove Tadzio from the older man's proximity. In fact, I was sort of visualizing an ending in which Tadzio dies of Cholera, and Achenbach is racked with guilt, possibly even driven totally mad with guilt)

Of course, when the object of your obsession is only 14 years old, not making contact can probably be seen as the nobler action to take than to make contact; and sticking to stalking behaviour is probably preferable to some potential alternatives.

In spite of my criticism of Mann's ideas and of his patches of overwrought, overemotional purple prose, the latter suits the subject of the story well, and there are certainly a lot of thought-provoking ideas and well-executed imagery.

Mann also displays keen insight into his characters. He portrays the aging, smitten homosexual well, and the dissolution of his personality via the intensity of his obsession is conveyed with pathos despite the relentless dissection under Mann's unnerving microscope.

One feels torn between pity for Achenbach while at the same time suppressing a shudder at the creepiness of his stalking behavior - but Mann manages to make him look pathetic more than anything else.

Mann also remarks on Tadzio's narcissism with acute insight. According to [b:The Real Tadzio: Thomas Mann's Death in Venice and the Boy Who Inspired It|75427|The Real Tadzio Thomas Mann's Death in Venice and the Boy Who Inspired It|Gilbert Adair|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1170875167s/75427.jpg|72963], the latter was indeed a pretty narcissistic person who enjoyed the attentions of older men, so Mann was pretty spot-on with his portrayals.

All-in-all, as with all good fiction, the novel leaves one with conflicted feelings. And, like all good fiction, it makes you roll around its various elements in your head, considering and re-considering; trying to find definite stances. The fact that the latter is so hard to do with this work of fiction, is a part of what makes it good fiction, whether one agrees with all of the specific ideas put forward by it or not.

---

I must mention that I started the novella with the e-book version of the translation by Michael Henry Heim, and finished with the translation by Clayton Koelb, with some cross-over where I read passages out of both. The latter claims to be the most natural and most US-friendly translation out there, but these two translations appeared fairly similar to me.

We're having an open book discussion of this book here . Do come and join!

We're having an open book discussion of this book here . Do come and join!

Wow, more & more, when it comes to China Mieville, for me, it's lurrvve lurve LURVE! I'm starting to get to the point where I miss his 'voice' when I'm not busy reading a Miéville...

In this amusing and inventive coming-of-age story, Miéville pulls out all the Postmodernist stops & creates a work that is at the same time immediate, as it is highly allusive & metafictional.

Some of the characteristics of Pomo fiction, especially as they apply to Railsea:

Postmodern authors tend to employ metafiction (fiction that refers to itself, for instance when it poses as a journal or a history book, or when the author (as Miéville does in this novel) "breaks the fourth wall" by speaking directly to the reader).

Another characteristic of postmodern literature is the questioning of distinctions between high & low culture through the use of pastiche. A pastiche is a work of art or literature, that imitates the work of a previous artists, usually distinguished from parody in the sense that it celebrates rather than mocks the work it imitates. It tends to combine subjects & genres not previously deemed fit for literature.

In plain terms, this would mean that lines between media and genres are being blurred, especially those between, in this case, speculative and literary fiction, and... whatever genre of the works alluded to, I'd imagine.

David Mitchell's Cloud Atlas (the one that was recently adapted into a film) is a good example of pastiche, especially in a chronological sense.

Common themes & techniques in pomo fic:

In Railsea, we find a lot of instances of parody and of intertextuality.

I'm going to shamefully steal Wikipedia's paragraph on intertextuality because it perfectly describes what Miéville does in this novel:

Intertextuality

Since postmodernism represents (an integrated) concept of the universe in which individual works are not isolated creations, much of the focus in the study of postmodern literature is on intertextuality: the relationship between one text (a novel for example) & another or one text within the interwoven fabric of literary history.

Intertextuality in postmodern literature can be a reference or parallel to another literary work, an extended discussion of a work, or the adoption of a style. In postmodern literature this commonly manifests as references to fairy tales – as in works by Margaret Atwood, Donald Barthelme, & many other – or in references to popular genres such as sci-fi & detective fiction.

Often intertextuality is more complicated than a single reference to another text.

Indeed, Miéville makes many allusions to varied sources, some of them less respectful than others, but most of them pretty funny in a dry, tongue-in-cheek sort of way.

The main work that Miéville parodies here, would be Moby Dick by Herman Melville, first published in 1851 . The latter is ... wait, let me utilize Wikipedia again:

==========

Moby-Dick; or, The Whale ... is considered to be one of the Great American Novels. The story tells the adventures of w&ering sailor Ishmael, & his voyage on the whaleship Pequod, comm&ed by Captain Ahab. Ishmael soon learns that Ahab has one purpose on this voyage: to seek out Moby Dick, a ferocious, enigmatic white sperm whale. In a previous encounter, the whale destroyed Ahab's boat & bit off his leg, which now drives Ahab to take revenge.

In Moby-Dick, Melville employs stylized language, symbolism, & the metaphor to explore numerous complex themes. Through the journey of the main characters, the concepts of class & social status, good & evil, & the existence of God are all examined, as the main characters speculate upon their personal beliefs & their places in the universe.

The narrator's reflections, along with his descriptions of a sailor's life aboard a whaling ship, are woven into the narrative along with Shakespearean literary devices, such as stage directions, extended soliloquies, & asides.

The book portrays destructive obsession & monomania, as well as the assumption of anthropomorphism.

========

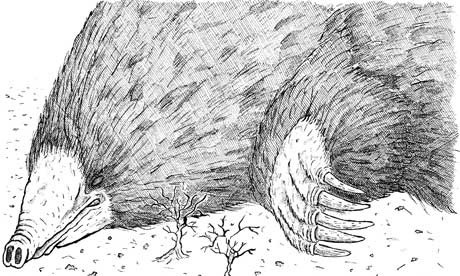

In Railsea, the names & a gender & a limb or two & a few species are changed, not to mention the landscape. In Railsea, we are looking for our malicious prey, which is a huge mole instead of a whale, while travelling the "railsea" instead of the ocean, in a train instead of a ship. ..& we have more fun. Lots more fun.

Miéville pokes merciless fun with many aspects of Moby Dick, (& other works) to the point that I often laughed out loud. Which brings me to another set of characteristics of po-mo fiction, which fits in with the parodic style of Railsea, being: irony, playfulness & black humor.

Well, these are in ample supply in Railsea. Miéville is pretty inventive with his world-building (Miéville readers know that by now) & in this work, in addition, he peppers the text with clever writerly asides & well-executed drawings.

Moby Dick is not the only text he alludes to though; the text is richly scattered with allusions to especially "adventure" or "boy's" fiction like Kidnapped & Treasure Island By RL Stevenson, including a truly hilarious reference to Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe. Not sure what else; but here is the list of the most important influences as supplied by CM himself:

Joan Aiken, John Antrobus, the Awdrys Sr. & Jr., Catherine Besterman, Lucy Lane Clifford, F. Tennyson Jesse, Erich Kästner, Ursula le Guin, John Lester, Penelope Lively, Spike Milligan, Charles Platt, & the Strugatsky Brothers.

Wondering about the &? Seems like another Mieville experiment in text==> meaning. The amper&and& symbolize the twisting of the railtracks. I'm not sure if that particular little experiment worked (replacing "and" with "&"), since it seems to irritate many readers, but I must admit that after initially being irritated myself, I soon got used to it & didn't even notice it anymore by the end.

This is one of the things I love about China Miéville: he is courageous! He is prepared to put his money where his mouth i&.

China, I <3<3<3<3 you !!! XOXOXO </b>

Looking forward to your next creation.

Full disclosure: Okay, this work is not perfect, perhaps especially due to a curious emotional 'dryness' or restraint. New Moon it is not.

In some respects this makes it a bit dry and nerdy compared to "non-literary" YA fiction out there.

...but if you're a nerd, this provides so many chuckles that it is worth its 5 &tars. Part of why I gave it 5 stars, was because I think China has gained some immense discipline as a writer. A good thing is that Miéville has, for a change, pared down the plot a lot compared to some of his initial works - albeit almost a bit too much this time. On the other hand, stylistically, for me, this work is perfect.

*All illustrations shown here, are from the book, as done by China Miéville himself.

.

*With thanks to Wikipedia, where you can read more on po-mo fiction: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postmodern_literature

The book would have received a 5 star rating from me if it had been more up to date. However, environmentalism is a time sensitive subject, and most of the texts included in this anthology date from the mid-nineteen nineties.

The book would have received a 5 star rating from me if it had been more up to date. However, environmentalism is a time sensitive subject, and most of the texts included in this anthology date from the mid-nineteen nineties.On the scientific front, we know quite a bit more than we did then. However, many of the prophecies in the book have turned out to be as spot-on as can be expected. Also, it is a nice introduction into the issues, and presents quite a nice scope of the various approaches to environmental philosophies.

Be that as it may, I would rather recommend something more up-to-date to anyone interested in the field.

Ah, being the upcoming publication of the author who wrote:

Ah, being the upcoming publication of the author who wrote:"But thine eternal summer shall not fade

This is in no way due to global warming;

Nay, from thy breasts shall verses fair be made

So damn compulsive they are habit-forming

So long as men can read and eyes can see

So long lives this, thou 34DD "

and

“There's nothing wrong with giving up all your principles for a suitable financial reward. It is indeed the basis of our society.” ,

this is certainly a space on the literary horizon to watch with anticipation. The question remains to be seen what he will deem to be a "Suitable financial reward". That is the question.

The other question is: Will I be able to read it onscreen?

The story 'Boy in Darkness' was so strange and uneven, that I'm not sure what to make of it.

The story 'Boy in Darkness' was so strange and uneven, that I'm not sure what to make of it.It seems to be some kind of sarcastic religious allegory, but the satire doesn't seem to really fit into any specific recognizable pattern of what exactly it would be satirizing.

The Lamb would certainly seem, by its symbolism alone, to be a metaphor for Jesus Christ, but its attributes definitely don't correlate with that of Christ; if anything, rather with those of the older Judaic religions. (The forerunners of Christianity and source of the Old Testament.)

I kept wanting to put the lamb into the place of the Christian church, and the goat and the hyena into that of its main arms, being all the reformist churches and the Catholic church, but I couldn't quite figure out which would be which--the goat the reformed churches perhaps, and the hyena the Catholic church?

I can see what he did there, saying that religion takes away one's identity and individuality, and turning one into a blind sycophant (only, in this case it is the lamb that is blind?)?

But all those hyperbolic adjectives: "horrible" "evil" and so forth, not to mention the particularly excessive recurrence of the words "dead", "death" "deadly and "deathly"; pushes it rather over the top. Well, the adjectives I just mentioned will give you a good idea of the atmosphere in the story, winkety wink. I might add that it is rather purple in that sense too. Purply deathly prose, ha.

In any case, the comparisons that you need to make to see it as satire seem so incongruent and ill-fitting, that although I spotted a few good ideas there, I finally gave up on the religious metaphor idea and tried to see the story as a pure flight of fantasy.

..but even as a flight of fantasy the whole thing seemed rather...

Let's just say that the three stars are for the fact that it's pretty imaginative and that Peake throws around a few interesting ideas regarding the power of the mind and the power of humans' need for belonging, acceptance and recognition.

The Peake short story "Danse Macabre", that came along with my copy of Boy in Darkness, felt a lot more fun to read. Danse Macabre is something more in the Gothic horror ghost story tradition. It is clothed in the typical Gothic sense of drama, although Peake's sense of humor can be caught twinkling at you through the interstices with this one. I would award the latter story closer to four stars, for its entertainment value, and for being a quite excellent example of Gothic horror.

Though The Hollow Men is more stark and elegant than Eliot's complex poem, The Wasteland, one could still end up spending hours if you were to dissect this poem line by line.

Though The Hollow Men is more stark and elegant than Eliot's complex poem, The Wasteland, one could still end up spending hours if you were to dissect this poem line by line.Whether one agrees with Eliot's sentiments and his personal philosophy or not, his imagery is simply superb.

Bleak bleak bleak outlook. One has to applaud the sheer force of the imagery. What could be more disturbing than a procession of brainless, shuffling zombies? Possibly a horde of sightless, shuffling strawmen, hollow at the core, leaning against one another to remain upright, whispering with dry voices, whispering, whispering, with arid voices like the rustle of wind through the dry grass... whispering like rats feet scurrying over broken glass in a dank subterranean cellar...

Can you see it in your mind's eye?

That could be “us”, that could be mass culture, consumerism. I do think that Eliot meant to include secularism into his aspect of hollowness, but it needn’t be read that way; in fact, it can be any cultural situation that espouses “hollowness” , and it can be any lack of deep values.

This is what makes the poem so classic; because of its bareness, its bleakness, its muted though deeply effective, controlled imagery, it can be used as a basis for almost any contextual interpretation that you’d care to tack on to it.

...and then of course, there is the subtlety... The sheer subtle genius of passages such as:

Shape without form, shade without colour,

Paralysed force, gesture without motion;

and

Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow

and

Between the conception

And the creation

Between the emotion

And the response

Falls the Shadow

and

Between the desire

And the spasm

Between the potency

And the existence

Between the essence

And the descent

Falls the Shadow

Eliot was apparently pretty depressed when writing it, and it shows; even more than with The Waste Land.

Note that he speaks of The Hollow Men as "us". So he is including himself here, possibly his whole generation.

There is a deep despair here, a horror; the horror of nihilism staring up at you from the darkness; a deep black gulf of nothingness. If poems were to be classified into the same genres as prose, this would be one of my favorite horror poems; it is darker, certainly, than anything Poe has written.

Re-reading this poem made me realise that I REALLY need to brush up on guys like Kierkegaard, Camus and Sartre.

Noting what some critics 'see' in this poem, makes me smile a little, but then, the poem lends itself so well to possible allusions, and of course, Eliot is known as very allusive poet; an image which he himself was quite eager, it seems, to enforce.

No doubt most of the allusions were deliberate, and of course many clues were planted by the erudite Eliot in person. But even if this poem contained not a single literary reference or allusion; just as it stands by itself, it already oozes a frightful, horrific genius sheerly via its evocative power alone.

Although the poem is probably more meant as an an attack against the loss of idealism and as an attack on secularism and/or atheism, and though it smacks of the despair created by the threat of meaninglessness and absurdity that existentialism sneaks into our world view, (the poem seems to have quite a few allusions to covert subversion), I can personally apply it to a more modern frustration with mass media culture (which was of course not quite as prevalent as it is now, back in 1925 when the poem was written).

Since I do think Eliot himself was at a pretty low point psychologically when he wrote this, it sort of touches one with its notes of personal anguish too. So, for me, this poem can be read both on a personal and on a societal level.

Ugh. Is the book as unrelenting in its parade of unrelenting, sicko violence as the show has become?

Ugh. Is the book as unrelenting in its parade of unrelenting, sicko violence as the show has become? I really enjoyed the HBO show until about 3 episodes ago, (ep.4) when the sick torture and unrelenting violence came back again. Gratuitously cruel and senseless violence seems to be becoming all that there is to see here. I enjoyed the series at the start, because it seeemed to be building up to becoming a political thriller, but now seems hardly more than just an offering out of the torture porn genre.

Episode 4 was a real downer, (what happened with Jamie and his companion) although the end of that episode was quite enjoyable in spite of its violence, albeit what Dany did was predictable and expected. Then came episode 5, which redeemed it somewhat. After episode 6, I don't think I want to watch the rest of it anymore.

Ugh. :(:(:( I'd rather pull one of my toenails off and spare myself some time.

Or faster yet, break my own nose with a hammer. It will have more or less the same emotional effect. Actually, doing the latter might be preferable than suffering through more of the show...

Hmmm... rather inadequate as far as depth is concerned. Really, I can get more in-depth material off the internet just by Googling.

Sadly it's very short. It spans quite a few subjects, for instance a short bio, and some background and a short treatment of most of her works, but each of them not treated in much depth.

On the other hand, it certainly deserves at least 3 stars because it is quite adequate in scope, if not in depth.

So, if you don't know a thing about Virginia Woolf, this is indeed a good place to start, as the word "introduction" implies. However, if you have studied Virginia and her works a bit already, rather look for something more substantial.

Good day, Ladies and Gentlemen, today we’d like to introduce you to a new pair of literary specialists, just graduated from Bullford, and full of things they want to say.

Good day, Ladies and Gentlemen, today we’d like to introduce you to a new pair of literary specialists, just graduated from Bullford, and full of things they want to say.With no more ado, I shall hand over the discussion to Asterisk and Obstalisk.

ASTERISK: Thank you! Yes, we certainly have a lot to say.

OBSTALISK: *burp* Yeah! What are we gonna talk about today?

ASTERISK: We’re going to use some short stories (or perhaps a short story) by Poppy Z.Brite to wax forth on some aspects of Gothic fiction, or even maybe Southern Gothic fiction, because she actually falls into the latter genre.

OBSTALISK: Huhuhuhuh *snort* you mean that goth lady who isn’t a lady anymore.

ASTERISK: What do you mean, not a lady?..oh, that. Shut up, Obstalisk!

OBSTALISK: Why? It’s true! She’s not hiding it, she’s...

ASTERISK: *Gives O a backhander* We’re not here to gossip, but to talk about literature. I would like to talk about how Poppy Z. Brite uses sensual and conceptual contrasts and liberal use of metaphors and imagery in His Mouth will Taste of Wormwood to add a fresh, poetic and disturbing element to her rendering of the Southern Gothic style, and uses contrasts as a method of heightening a sense of the transgressive.